This story is part of Priced Out, CNET’s coverage of how real people are coping with the high cost of living in the US.

Brandon Douglas/CNET

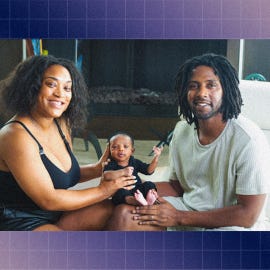

On a warm day last spring, Teja Smith, 31, went to Cedars-Sinai hospital in Los Angeles to go over her birthing plan. Instead, at just over 36 weeks pregnant, she learned she had preeclampsia, a serious high-blood-pressure disorder that can occur during pregnancy, and had to be induced immediately. Three days and an unplanned cesarean section later, Smith walked out with her newborn son and a $42,180 medical bill.

Though her insurance covered $40,000 of that bill, Smith was left with the remaining balance. “I was even charged for skin-to-skin contact with my son and my umbilical-cord cutting,” she said.

Teja Smith and family.

Smith’s story isn’t uncommon. The cost of childbirth in the United States is higher than in any other country. For parents with insurance, the average out-of-pocket expense for traditional childbirth is $2,854, while a C-section, like Smith’s, averages $3,214, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

If you don’t have insurance, costs can quickly spiral into tens of thousands of dollars. While there are resources available to help lower pregnancy-related expenses, there are still gaps in accessibility and huge disparities in medical care costs for the uninsured or underinsured.

Low-income pregnant people, from Black and Latino families in particular, are less likely to have health insurance, and these families spend an average of between 19{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac} to 30{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac} of their annual income on pregnancy and childbirth-related medical expenses. And that doesn’t include the hidden costs outside of labor that start in the family-planning stage, or the expenses that continue after delivery.

“My biggest advice is to never go into a pregnancy uninsured, even if it’s Medicaid or something that is state provided,” said Smith.

Pregnancy bills are steep — and the journey looks different for everyone

Shilpa Nandwani, 30, a teacher in Austin, Texas, always knew she wanted children. After getting married, in December 2021, Nandwani and her partner both decided to try in vitro fertilization, or IVF.

Shilpa Nandwani and her partner.

Nandwani’s insurance offered access to Progyny, an employer-sponsored fertility and family-building benefit. She and her partner went through the process of egg retrieval, which cost a total of $8,000 for everything, including the sperm donation, embryo genetic testing and frozen embryo transfer for both of them. Without the assistance of Progyny, their bill would have been $32,000.

Fertility treatments such as IVF and intrauterine insemination are becoming more common in the US — some 33{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac} of Americans have turned to fertility treatments or know someone who has, according to a Pew Research Center study. But these treatments come at a huge cost for those who undertake them.

“The road to parenthood isn’t always as easy as what we’ve heard from movies and storybooks,” said Janet Choi, a reproductive endocrinologist and medical director of CCRM Fertility Clinic in New York. Choi noted that one round of IVF with medication can cost more than $25,000, and it often takes two to three cycles to be successful.

Dr. Janet Choi: “The road to parenthood isn’t always as easy as what we’ve heard from movies and storybooks.”

An employer-sponsored fertility benefits program is critical for those who need to go this route, according to Choi. “It can help not only offset the financial burden of fertility treatments, but can also support the mental and emotional strain of going through the process,” she said.

Conception costs can leave parents-to-be with high medical bills, even before pregnancy begins. For many, the first expenses start after finding out they’re pregnant, during the prenatal term. Regular doctor’s appointments for exams, blood work, ultrasounds and other testing span $100 to $200 per appointment (most pregnant people attend 12 appointments over their pregnancy term). Genetic carrier testing, which may be required to detect certain congenital disorders, isn’t always covered by insurance and can add an extra $100 to $1,000 to out-of-pocket expenses.

Then there are prenatal vitamins, maternity clothes and pregnancy-safe skin care and makeup, which easily add up. For instance, Nandwani pays $50 for a two-month supply of prenatal vitamins — she estimates she’ll have spent $750 on supplements alone throughout her pregnancy and postpartum.

Childbirth is generally the priciest of all, and these costs may not be covered by your insurance if you opt for nontraditional childbirth methods, which have become more popular in the past five years.

Nandwani and her partner are choosing to give birth outside a hospital setting. “We decided to go the route of getting a doula and midwife because, as a queer couple, I also did not want people to question our parent titles and relationship with our baby,” she said. The couple will pay $2,000 for their doula and $5,000 for midwife services.

Finding health care coverage to lower pregnancy expenses

High doctor or hospital bills during pregnancy can lead to severe long-term consequences, including medical debt, bankruptcy and in some cases, worsening health outcomes. As many as 24{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac} of pregnant or recently pregnant women report having unmet health care needs, which can lead to adverse birth outcomes and other risks, according to a recent study in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Given that half of all pregnancies in the country are unplanned, households that don’t have insurance are left scrambling for medical care. Though employer-sponsored health plans and the public health insurance marketplace may offer low-cost options, the small open enrollment window, which typically falls between Nov. 1 and Jan. 15, could prevent expectant parents from enrolling. Getting coverage outside an open enrollment period requires a “qualifying life event” like starting a new job, getting married or losing your existing coverage. Giving birth is considered a “qualifying life event” but pregnancy isn’t. Depending on timing, some expectant parents may not be able to sign up for coverage at all, while others might be able to sign up toward the end of their pregnancy.

If health insurance isn’t an option, Medicaid may provide coverage. Lower-income pregnant people who meet state income requirements can qualify for reduced or even free Medicaid coverage, but there are still gaps in the system preventing coverage for broader maternal and child health care. And, though the majority of states have implemented expanded coverage of 12 months for postpartum women, in some states, Medicaid benefits end 60 days after childbirth.

A further expansion of Medicaid benefits to offer affordable coverage to more pregnant people could not only decrease the financial burden on new parents, but also help reduce maternal mortality rates, which are higher in the US than in any other advanced country, according to the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute.

Resources to lower steep pregnancy costs

Whether you’re insured or not, there are options available to help lower your out-of-pocket pregnancy expenses.

Nandwani has taken on contract work in addition to her full-time job, a financial solution that’s working well for her family. Though this option may be pragmatic for some, it may not be recommended for those with high-risk pregnancies. Working more than 40 hours a week while pregnant has been linked to serious health risks, including miscarriage and preeclampsia.

You may also be able to negotiate some of your medical expenses if you can demonstrate financial need. “Some hospitals allow you to submit financial records if you are unable to pay for certain things or agree to a payment plan,” said Smith.

If you plan to pay out of pocket for all or some of your pregnancy care, let your health care provider know. It may be able to offer lower-cost care options or a discounted package rate, or if it’s unable to reduce prices, it may be able to refer you to a more affordable clinic or doctor.

For uninsured parents-to-be who don’t qualify for Medicaid, there are other programs and resources. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children, or WIC; Children’s Health Insurance Program, also known as CHIP; and Planned Parenthood all offer low-cost pregnancy care service. The US Department of Health and Human Services also has a list of resources to help pregnant individuals find access to free or lower-cost services.

Connecting with others in your community or across the nation through Facebook groups and other online forums is a great way to share cost-reducing tips. Talking to other pregnant people or new parents may help better prepare you for the financial expectations, while offering solutions others have implemented. The Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania has a collection of different groups expectant parents can explore.

“Find support in whatever ways you can,” said Nandwani. “Part of the support is talking about finances with your partner or family and understanding the potential costs.”