Until three years ago, I thought I was brave. After all, I’m a girl who has trekked all the way across the Andes without a map. But there’s one thing that scares the hell out of me: getting pregnant.

It’s late 2018 and I’m 38 years old. I have always wanted to start a family, and I’ve reached a stage in life when doing so would make sense. I’ve established a career as a freelance journalist, and I’ve finally found the right man. We’ve been together for a year now; family and friends have begun watching closely to see if I’m still drinking alcohol.

What they don’t know is that fear has begun to consume my life. I’m plagued by a question that won’t go away: what if I give birth to a disabled child?

Most of my friends don’t think it’s such a big deal: there are prenatal diagnostic tests, after all. In Germany, where I live, antenatal screening is offered to all women over 35. I have always resisted going down that route, on principle. Because my brother has Down’s syndrome; because I want people like him to continue to be a part of our society. I had a great childhood, not despite my brother but together with him.

And yet the questions won’t go away. If I get pregnant, what diagnostics would I opt for? And what would I do with the results? Just asking them feels like betrayal.

Fear begins to creep into my body. Before long, I develop frequent back pains and, after a few months, I have to stop working: I have two herniated discs. I try to convince the world, and myself, that it’s not a big deal. I have an MRI and go through physical therapy and rehab, but nothing helps. I am appalled by my doctor’s insinuation that the whole thing could be psychosomatic. I can’t sit or lie down – the pain fades only when I walk. I spend nights pacing through my neighbourhood, Berlin’s hip Neukölln district, in tears, afraid that I’m losing my mind.

What’s wrong with me? I start looking for answers. I join a group on Facebook where adult siblings of people with disabilities discuss their experiences. Tentatively, I type: “I want to have a child, but I am terrified that it might be disabled. And I despise myself for feeling this fear. Do you know what I’m talking about?” I hit “Enter” and close my eyes in shame.

By evening, several women have responded. One offers a definitive answer: having a child is out of the question for her; she feels that she has too many responsibilities already. Others voice concerns about potentially hereditary genetic defects they might pass on, fears of oxygen deprivation at birth and of relationships destroyed by a disability in the family. Reading the responses, I can’t help but cry. But they are tears of relief. I can feel the pain behind the words – and finally I can understand my own suffering. I’m not alone.

Around 2.3 million people in the UK have a brother or sister with a disability, according to the NGO Sibs. In Germany, the number is thought to be somewhere between 1 and 4 million. Exact figures are hard to come by here. Statistics on disabilities and birth defects are not centrally collected, and for good reason: under Aktion T4, the Nazis’ euthanasia programme, an estimated 70,000 people with disabilities or other afflictions were murdered. Across Europe, the total number of victims was between 200,000 and 300,000 – people who, even today, have not received the same recognition as other victims of the Holocaust.

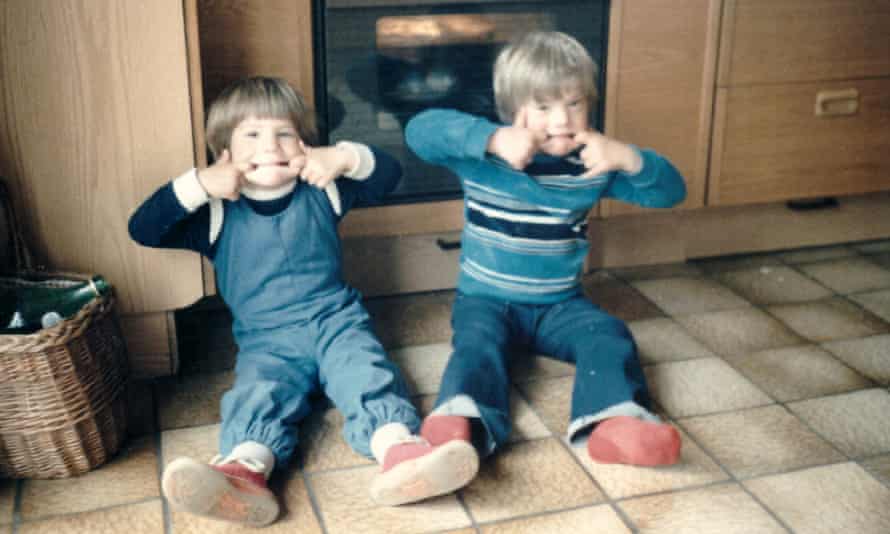

Just reading about this triggers a memory from my childhood. I’m four years old and walking down the street in front of our house, holding hands with my brother David, who is two years older than me. The farmer we buy milk from, a man of the war generation, leans over the fence. “That wouldn’t have happened under Hitler,” he says.

I know how furious my mother got when she heard such things, and how speechless. But I also know it was good for us to grow up in a small town in the Black Forest. Everyone knew my brother. People would give him sausages, and if he managed to sneak out of the house without anyone noticing, they would bring him home.

Still, words like that leave a mark. In retrospect, I understand why I was constantly on the lookout, ready at a moment’s notice to physically fight for my brother.

I begin to realise the tormented silence I keep about this issue isn’t just about me – it’s also an attempt to protect my family. I am building a fortress to shield a vulnerable interior from anything harmful outside.

Sign up to our Inside Saturday newsletter for an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the making of the magazine’s biggest features, as well as a curated list of our weekly highlights.

The world I live in seems to be one of hopeless contradiction. Everywhere, people talk about inclusion and celebrate diversity. People with Down’s syndrome sit exams at school and walk down the catwalk as models. At the same time, this world does all it can to sniff out these people in the womb; to eliminate them. Researchers in the US are working on “curing” the syndrome with the help of the gene-editing tool Crispr-Cas9. In the UK, the number of babies born with Down’s syndrome has dropped by 30{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac} in NHS hospitals that have introduced new, non-invasive prenatal tests. In Denmark, hardly any children with trisomy 21, the genetic anomaly that causes Down’s, are born any more.

My brother is no mistake, and nor are the lives my parents have led. They are, rather, an unbelievable achievement in a society that offered them only paltry support. In no way do I want to be misunderstood, and nor do I want to provide any fuel to a world already intent on eliminating anything that is different. And this is why I kept my burden to myself for so long: the feeling that my life would be over if I gave birth to a child with a disability.

At a routine appointment, my gynaecologist asks about my plans for starting a family. I tell her that I’m afraid. I simply can’t have a child with disabilities, for reasons I can’t satisfactorily explain, not even to myself. And aborting one is similarly out of the question.

By now I am 40 and my statistical likelihood of giving birth to a child with trisomy 21 is slightly more than 1{7b6cc35713332e03d34197859d8d439e4802eb556451407ffda280a51e3c41ac}, the same as for any woman my age. Ninety-five per cent of Down’s cases, including my brother’s, are the result of a spontaneous genetic mutation rather than heredity.

The gynaecologist dismisses my fears. “But the diagnostics will show us that,” she says. “Don’t worry.” My heart jumps into my throat as I think about the dilemma that would present. By then it’s too late, I want to say. I’m relieved when she changes the subject.

Once again, I don’t say what’s really bothering me: the feeling, for example, of leaving my brother David further and further behind. My brother, who was my companion and my accomplice throughout childhood. For whom I spoke when he fell silent for a few years as a small child, out of frustration that nobody understood him. For whom I spent years looking for some magic incantation that could make him “normal”. My brother, who sings loudly on the swing and concentrates so devotedly when drawing pictures, then as now. Who can love more wholeheartedly and deeply than anyone else.

David turned 44 last summer. Like me, he has moved out of our parents’ home, but he will never be able to live independently. He has wanted a girlfriend for years, but has never found one. Like most people with Down’s syndrome, he will never have children. It’s not my fault; it’s nobody’s fault. Yet that’s sometimes how it feels. Why him? It could have been me.

It’s autumn 2019. My back feels better, and I can work again. My boyfriend has turned out to be the most loyal and faithful partner I could wish for. This man would never leave me in the lurch with a child, no matter what that child can or cannot do.

During my search for other adults in my situation, I learn that siblings such as myself often have a hard time finding a partner – that they have a tendency to assess every candidate on the basis of how they get along with their disabled sibling. But when they finally find someone who passes that test, the relationship usually endures.

I want to know how women in similar situations are dealing with the issue that is tormenting me. Again, I post the question on Facebook. Most of the answers come from women of different ages and circumstances.

Charlotte (not her real name) is 27 and grew up with three brothers, all of whom are severely autistic. She has a healthy toddler. But the path to where she is now wasn’t an easy one. “It was clear to me that I didn’t want a disabled child. I’d just had enough,” she tells me. There was no way she wasn’t going for genetic testing, but she says of the doctor she saw: “He was totally cold, no empathy.” The results were unclear. Autism can be passed down genetically, but nobody really knows how, and there are no prenatal diagnostics. “Would you have had an abortion?” I can hear my voice getting shaky. “Yes, of course,” Charlotte says. She adds that she wouldn’t have been able to believe her bad luck. “I’d have thought: hello, fate? Have you completely lost it?”

I flinch – but I’m also impressed by her clarity. Other people I speak to tell me of childhoods filled with night-time care duties and cleaning up drool. Of wiping bottoms and childhood violence. Of course, the people who respond to my query don’t amount to a representative sample. But there are an impressive number of them. Over time, I talk to at least 50 women and men. Increasingly, I start to wonder why I am turning my own situation into such a big deal. When it comes to disabilities, after all, Down’s syndrome is certainly on the sunny side.

Little is known about the effects of a child’s disability on the lives of their brothers and sisters. I come across the nurse-scientist Sabine Metzing. She wrote her dissertation about children who provide nursing care to family members. She describes them as “individuals who have no choice”. They are “readily available” and always prepared to jump in where necessary. It sounds kind of brutal. That’s not me, I tell myself.

It’s almost an article of faith among such siblings to avoid talking about it. As adults, they are more likely to suffer from depression, allergies or, I’m interested to discover, chronic back pain.

There was a lot of life and love in our home – hugs, birthday parties and merriment. Sure, I helped take care of my brother. I was constantly out and about with him, especially as children. It seemed normal to me that he was slower and needed a lot of help. I was nine when he developed diabetes. I remember how he would rifle through the pantry at night, driven by poor diabetes control and cravings. I recall diabetic shocks and my mother’s desperation. Later, from the age of 12, I would often take on the task of measuring his blood sugar levels and giving him insulin injections – especially when my mother, who developed health problems of her own, was away for physical therapy at a clinic, sometimes for weeks at a time.

It never felt like a burden. Quite the opposite: I was proud of being so responsible and independent. When I see teenage girls now, I envy how carefree they seem. I am amazed at the confidence that I, being the youngest, had back then.

Dr Florian Schepper, a psychologist at the Leipzig University hospital, is one of the few researchers focusing on the siblings of people with disabilities. Since 2006, he has been working with groups of children and young adults who have chronically ill or disabled brothers or sisters, or whose siblings have died. I ask him what kinds of things they tend not to be able to see in themselves. “The burden they carry,” he says. “No matter how well a family meets the challenge, healthy siblings are always in a special situation, for their entire lives.”

It is, he says, most apparent at the time of major life events: “When important decisions about their own lives must be made, when it’s about self-fulfilment, siblings find themselves facing dilemmas that others can’t even imagine. It produces great stress.” It’s extremely helpful to hear this from an expert. I feel as if I might not be quite as crazy as I thought.

My friends continue having children, and I am amazed at their nonchalance about it. My attempts to talk about my predicament become less frequent. I know that they mean well when they say things like, “You have to think positively” or, “Most children turn out healthy.”

Like me, Sarah (not her real name) has a brother with Down’s syndrome. Six weeks before I talk to her, the 36-year-old gave birth to a healthy baby. “It cost me three years of hand-wringing,” she says. “The feeling of being alone with it was awful.” Sarah says she didn’t want to discuss her fears with her family. “I know my mother feels guilty on my account. Speaking about the burden would be extremely hurtful to her.”

I love my family. But at the same time, it is hard to talk to them about my fears. It took a long time before I found the courage to discuss it with our eldest brother, though he has already taken the plunge and become a father.

Sarah didn’t have any antenatal tests: “Ending my pregnancy would have been a betrayal of my brother.” She told her family at Christmas that she was pregnant and, later, her brother sidled up to her during a walk. “He asked me: ‘What will you do if you have a child like me?’ I was so happy at that moment that I had already made my decision. I was able to tell him: ‘I’ll have you over so you can say hello.’”

Sarah says a lot of smart things, but one hits particularly close to home. “Sometimes I wonder what took me so long? I think it had something to do with avoidance – the feeling that if I decided to have a baby, then I was taking a step away from my childhood family. I still provide a lot of support. It took a while to allow myself to start my own family, and to distance myself a bit.”

It chimes with something that has weighed on me since I began realising that my brother was different from me: at some point, my parents will no longer be there, and it will be extremely likely that I will play a significant role in caring for him. Following my father’s death seven years ago, my older brother and I were both made legal guardians, along with my mother.

Being a legal guardian is a full-time job, one many brothers and sisters take over at some point. A study in the southern German state of Baden-Württemberg found that one in five adults with a disability live in the home of a sibling. “Whether or not the parents have such expectations, it is perpetually the elephant in the room,” Schepper says.

The fear of the dilemma a pregnancy could present has not disappeared. But at least I now understand it better. Not having a child isn’t a solution either. My brother gains nothing if I limit my own life out of love for him. On the contrary, he’s crazy about our eldest brother’s daughter, and constantly asks me when I am going to have a baby.

Now, finally, I can tell him: soon. It is November 2021 and I am in my ninth month of pregnancy. My back pains have vanished and in my belly a baby – fit as a fiddle – seems to be preparing for a career in boxing. Sometimes, I can hardly believe that I have made it this far. At some point, the moment came when I realised I didn’t want fear to define my life, no matter how big it was. I had only one option: trying my luck and stepping into the unknown. Without a map.

Ultimately, I took up all the diagnostics available, and felt terrible about it. I opted for an NIPT screening, a non-invasive blood test – a prospect as disturbing to me now as it had been two years ago. If I was going to know, I wanted to know as early as I could, and with as much certainty as possible. When I first made the appointment, I wasn’t entirely sure I would go. But in the week leading up to it, my mother suffered a mild stroke. She was taken into hospital for observation – and with our concerns focused on her, I realised that whatever might be happening in my belly, I had to know. Only then could I make a decision that, as a grown woman, I could live with. Even so, on the way to the testing clinic, I could have spat in my own face.

I was lucky. I didn’t have to make a decision. All tests were negative, and the high-resolution ultrasound I had a few weeks later didn’t turn anything up either. When the result came through, I wasn’t the only one crying with relief: my mother was, too. Now, where there once was fear, there is a feeling of complete amazement, coupled with gratitude. And the ardent hope that the birth will be straightforward. My brother, soon to be an uncle for the second time, is drawing pictures of babies in the womb. And he’s desperately excited.

Dunja Batarilo gave birth to baby Clara in January.